Kirk Knestis—CEO of Hezel Associates and ex-career and technology educator and professional development provider—here to share some strategies addressing challenges unique to evaluating Advanced Technological Education (ATE) projects that target outcomes for teachers and college faculty.

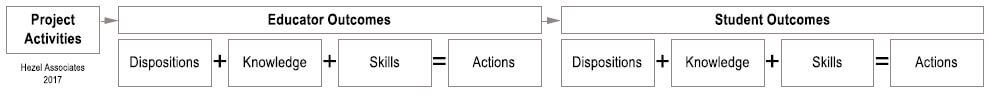

In addition to funding projects that directly train future technicians, the National Science Foundation (NSF) ATE program funds initiatives to improve abilities of grade 7-12 teachers and college faculty—the expectation being that improving their practice will directly benefit technical education. ATE tracks focusing on professional development (PD), capacity building for faculty, and technological education teacher preparation all count implicitly on theories of action (typically illustrated by a logic model) that presume outcomes for educators will translate into outcomes for student technicians. This assumption can present challenges to evaluators trying to understand how such efforts are working. Reference this generic logic model for discussion purposes:

Setting aside project activities acting directly on students, any strategy aimed at educators (e.g., PD workshops, faculty mentoring, or preservice teacher training) must leave them fully equipped with dispositions, knowledge, and skills necessary to implement effective instruction with students. Educators must then turn those outcomes into actions to realize similar types of outcomes for their learners. Students’ action outcomes (e.g., entering, persisting in, and completing training programs) depend, in turn, on them having the dispositions, knowledge, and skills educators are charged with furthering. If educators fail to learn what they should, or do not activate those abilities, students are less likely to succeed. So what are the implications—challenges and possible solutions—of this for NSF ATE evaluations?

- EDUCATOR OUTCOMES ARE OFTEN NOT WELL EXPLICATED. Work with program designers to force them to define the new dispositions, understandings, and abilities that technical educators require to be effective. Facilitate discussion about all three outcome categories to lessen the chance of missing something. Press until outcomes are defined in terms of persistent changes educators will take away from project activities, not what they will do during them.

- EDUCATORS ARE DIFFICULT TO TEST. To truly understand if an ATE project is making a difference in instruction, it is necessary to assess if precursor outcomes for them are realized. Dispositions (attitudes) are easy to assess with self-report questionnaires, but measuring real knowledge and skills requires proper assessments—ideally, performance assessments. Work with project staff to “bake” assessments into project strategies, to be more authentic and less intrusive. Strive for more than self-report measures of increased abilities.

- INSTRUCTIONAL PRACTICES ARE DIFFICULT AND EXPENSIVE TO ASSESS. The only way to truly evaluate instruction is to see it, assessing pedagogy, content, and quality with rubrics or checklists. Consider replacing expensive on-site visits with the collection of digital videos or real-time, web-based telepresence.

With clear definitions of outcomes and collaboration with ATE project designers, evaluators can assess whether technician training educators are gaining the necessary dispositions, knowledge, and skills, and if they are implementing those practices with students. Assessing students is the next challenge, but until we can determine if educator outcomes are being achieved, we cannot honestly say that educator-improvement efforts made any difference.

Except where noted, all content on this website is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

EvaluATE is supported by the National Science Foundation under grant numbers 0802245, 1204683, 1600992, and 1841783. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed on this site are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

EvaluATE is supported by the National Science Foundation under grant numbers 0802245, 1204683, 1600992, and 1841783. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed on this site are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.